Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (gastric bypass surgery) has been considered the “gold standard” for weight loss surgery. The reason for this is that this procedure has demonstrated predictable, impressive and durable weight loss with a low rate of severe complications. The procedure consists of two basic components: restriction and malabsorption.

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (gastric bypass surgery) has been considered the “gold standard” for weight loss surgery. The reason for this is that this procedure has demonstrated predictable, impressive and durable weight loss with a low rate of severe complications. The procedure consists of two basic components: restriction and malabsorption.

Restriction

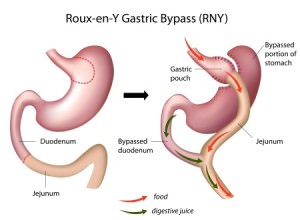

Restriction refers to the inability to eat large volumes of food. Presently, a large volume is what most of us would consider a “normal size” meal. To create restriction the stomach is divided using state of the art surgical stapling devices. A gastric pouch is created in a vertical fashion. The pouch remains attached to the esophagus (food pipe). The remainder of the stomach is left in its native position, however, there no longer remains a connection to the esophagus and therefore food no longer enters the majority of the retained stomach.

The initial pouch can accommodate approximately 20-40 ml in volume. The ability of the pouch to dilate and enlarge over time is a natural phenomenon referred to as “receptive relaxation”. Several years after the procedure an individual can expect to accommodate significantly more food.

Malabsorption

Malabsorption describes the effect of limiting the body’s ability to absorb calories from food in addition to certain vitamins and minerals. To perform a gastric bypass the small intestine is divided approximately three to four feet downstream from the stomach. The far end of the small intestine is reattached to the newly created stomach pouch. The proximal portion of the small intestine (the end of small intestine still in connection with the stomach) is reattached to the small intestine approximately 5 feet downstream (closer to the colon). This anatomical rearrangement effectively creates an anatomy where food and digestive enzymes have bypassed 40-60% of the small intestine limiting absorption of calories and other essential nutrients.

Weight Loss

When combined, the restriction and malabsorption promote rapid and steady weight loss. During the first 3-6 months there is dramatic weight loss and it is not uncommon for patients to lose 40 to 50% of their excess weight. Weight loss at one year is generally around 50 to 60% excess weight loss. Between 18 months and two years the weight loss from surgery has generally ceased. At this point some patients may have lost 60-80% of their excess weight.

An appropriate diet, dedicated exercise and an active lifestyle are paramount to maintaining weight. Reverting to old habits has a high probability of causing weight regain.

Video Overview

Complications in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

All surgery poses the risk of having a complication. Patients are at risk for complications that aren’t unique to bariatric surgery. Fortunately, the majority of complications that occur are generally not life threatening and can be managed without further surgery. Complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass are categorized as “early” and “late” complications. Early complications are generally those that occur right around the time of surgery or within the first 30 days. Late complications generally occur from one month to years after the procedure.

Early complications

Bleeding

Significant blood loss or hemorrhage is an uncommon event. The source of blood loss is usually from the dense network of blood vessels that surround the gastrointestinal tract. When the stomach or small intestine is divided there is the potential to damage adjacent vessels with resulting blood loss. Another source of bleeding that can occur after the surgery has been completed is from the staple lines created to form the gastric pouch or where the small intestine has been re-connected to itself. Staple line bleeding is usually “self-limited”, meaning it will likely stop on its own. Although the need for blood transfusion is uncommon it may be necessary as a life saving maneuver.

Perforation or “leak”

The most dreaded complication is a “leak”. Although there are two points of newly created connections after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass the overwhelming majority of leaks occur at the connection between the gastric pouch and small intestine (gastrojejunostomy). A leak can be devastating if not managed quickly and appropriately. A leak can lead to peritonitis, a potentially deadly form of intra-abdominal infection. The risk of having a leak has been estimated to be around 0.25-1.0%.

Deep Vein Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism

DVT (deep vein thrombosis) describes a blood clot that forms within the veins of the pelvis or leg. A DVT can cause leg swelling and pain. A DVT becomes more problematic if the clot dislodges and travels to the heart and is then pumped into the pulmonary (lung) arteries. This is referred to as a PE (pulmonary embolism). A PE can place significant strain on the heart and if left untreated can have major consequences. Treatment requires the use of a blood thinner for a period of 3 months to a full year. In some cases, medical treatment with a blood thinner could be life-long.

Several precautions are taken to reduce the chances of developing a DVT/PE. This includes the use of blood thinners prior to and after surgery. In some patients blood thinners may be necessary even after discharge. In addition, SCD (serial compression device) boots are placed on the patients lower legs prior to surgery and remain in place until the patient is up into a chair and walking.

The risk of developing a DVT depends on a number of factors. Dr Laker will be able to give you an idea of what your risk is based on your history and a number of other factors. Overall, the risk of developing a DVT is quite small, approximately 0.5-2%. Of those patients who develop a DVT the risk of having a PE is also very low.

Wound infection

Infections at the incision sites are uncommon when the procedure is performed in a laparoscopic fashion. However, should your operation need to be converted to an open procedure there is a substantially higher chance of developing a surgical site infection. Post-operative wound infections can generally be treated with local wound care (dressing changes) and potentially a course of antibiotics.

Death

Large studies have demonstrated the potential of dying as a result of complications after gastric bypass surgery are very low and around 0.25%.

Late complications

Marginal ulcer/stricture

A marginal ulcer is a superficial erosion along the small intestine at the junction of the gastric pouch and small intestine connection (gastrojejunostomy). Patients often report the sensation of pain or discomfort as food enters the gastric pouch. Some patients will experience nausea or vomiting shortly after eating. A marginal ulcer can develop within weeks to several months after surgery.

A stricture is a dense scar at the connection between gastric pouch and the small intestine and can produce similar symptoms as a marginal ulcer. Strictures create an obstruction or blockage as food passes from the gastric pouch and into the small intestine. Strictures generally develop within weeks after the procedure and are unlikely to form months later unless it is the result of an untreated marginal ulcer or fistula.

It can be very difficult to differentiate a stricture from a marginal ulcer based on symptoms alone, especially in the first several months after surgery. Fortunately, the procedure performed to diagnose these complications is exactly the same. An endoscope (small tube with a camera on the end) can be passed from the mouth and into the gastric pouch allowing the surgeon to differentiate between the two complications. This diagnostic test is performed routinely as an out patient procedure. In some instances patients can have both a stricture and a marginal ulcer.

The treatment of marginal ulcers generally requires the patient to take antacid medications twice daily and a liquid medication (Carafate) 3-4 times per day for 6 to 12 weeks. Marginal ulcers can bleed and even perforate on rare occasions and require emergent surgery to correct. There are certain medications that can increase the chances of developing an ulcer and these must be avoided. The most common medications are: aspirin, Motrin, Alleve and other NSAIDs. Smoking and alcohol are also major risk factors.

Strictures can be dilated during the endoscopy. This essentially “stretches” the connection and allows food to more readily pass across the connection. In some patients repeated endoscopies may be necessary until the stricture has been appropriately dilated.

Intestinal obstruction

Intestinal obstructions are usually caused by a mechanical blockage of the small intestine. The majority of intestinal obstructions after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass are the result of either adhesions (scar tissue) or internal hernias. Adhesions are bands of scar tissue that can form after surgery and can pinch or trap a segment of small intestine. There is no way to prevent the formation of postoperative adhesions, however, adhesions are much less likely to form after a laparoscopic procedure. Internal hernias are the result of dividing and re-routing the small intestine. The post-surgical anatomy creates potential spaces that can trap a loop of small intestine leading to an obstruction.

Fistula

A fistula is abnormal connection between two hollow organs. In the case of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass the gastric pouch can fuse and erode into the old stomach (remnant stomach) creating an abnormal connection between the two structures. This can be the source of a chronic, non-healing marginal ulcer or stricture. Sometimes the fistula can be treated and closed endoscopically and at times may require surgery to correct.

Vitamin/mineral deficiencies

The nature of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass predisposes the patient to poorly absorb certain vitamins and minerals. Malabsorption of vitamins and minerals can usually be managed by taking the vitamin and mineral supplements as recommended by Dr Laker. Blood work should be obtained twice annually for the first year or two after surgery and then annually.

Gallstone formation

Rapid weight loss can predispose patients to develop gallstones. Should the gallstones become symptomatic patients may require gallbladder surgery.

Kidney stones

The absorption of various chemicals and nutrients in the intestine after gastric bypass can predispose to the formation of a certain form of kidney stones. Appropriate hydration is a key factor in avoiding the formation of kidney stones. Individuals with a history of kidney stones may have an increased risk of developing additional stones after bypass surgery.

Hernia

Hernias at the incision sites are uncommon when the procedure is performed laparoscopically. However, should your operation need to be converted to an open procedure there is a substantially higher risk for developing a hernia. Wound infections also increase the chances of developing a hernia as does obesity and diabetes.

Regaining Weight

Approximately two years after surgery some patients will regain 5-10% of the total weight initially lost. In time, the gastric pouch dilates and can accommodate larger volumes of food. In addition, the segment of small intestine available to absorb ingested calories will become extremely proficient. An appropriate diet, dedicated exercise and an active lifestyle are paramount to maintaining weight. Reverting to old habits has a high probability of causing weight regain.