What is GERD (Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease)?

GERD or gastroesophageal reflux is one of the most common chronic conditions treated by medical physicians. Over 65% of individuals will experience symptoms of reflux on an annual basis. Ten to 15% of people will have recurrent episodes throughout a week’s time.

GERD or gastroesophageal reflux is one of the most common chronic conditions treated by medical physicians. Over 65% of individuals will experience symptoms of reflux on an annual basis. Ten to 15% of people will have recurrent episodes throughout a week’s time.

Symptoms are often described as a “burning sensation” behind the sternum, within the neck or at the back of one’s throat. Many times the symptoms are after eating or drinking, often made worse while lying flat or bending over. Belching or regurgitating undigested food is not uncommon. Long standing reflux can lead to a number of other symptoms often overlooked or not attributed to reflux disease. Other condition associated with long standing reflux include: recurrent pneumonias, worsening asthma symptoms and voice changes. Repeated episodes of micro-aspiration (stomach contents entering the airway) can lead to these conditions. If left untreated or under treated reflux can cause inflammation of the esophagus. Over time inflammation can lead to scar formation or a stricture within the esophagus making swallowing food very difficult and a painful experience. One of the most worrisome complications of long standing exposure of the esophagus to gastric contents is the development of “Barrett’s esophagus”. This term describes the microscopic changes to the lining of the esophagus and has been demonstrated to be an independent risk factor for developing esophageal cancer. When identified early and appropriately managed this condition can be controlled and even reversed.

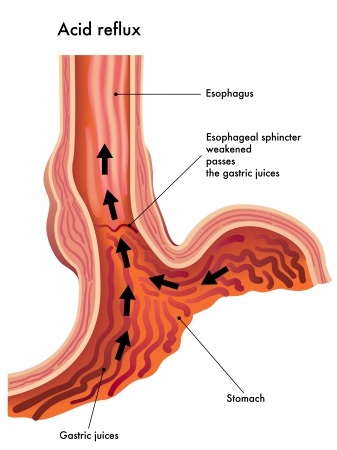

The cause of reflux is best explained by thinking off the lower esophagus as a muscular, one-way valve. When the valve is disrupted as a result of anatomical change the chances of the valve working effectively are reduced. The most common cause for an anatomical disruption is a hiatal hernia.

The esophagus traverses the chest and enters the abdomen through an opening in the diaphragm called the esophageal hiatus. In some individuals this opening can widen and permit the lower esophagus and stomach to slide up and into the chest. This anatomical change disrupts the inherent mechanism that prevents food, liquids and stomach contents from entering the lower esophagus thereby leading to reflux and its symptoms.

There are many other causes for reflux that are not always attributable to failure of the lower esophageal sphincter. The more common causes are below:

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Alcohol

- Smoking/tobacco use

- Certain prescribed medications

- Dietary factors: spicy food, peppermint, soda, tomatoes, vinegar, citrus fruits, chocolate, caffeine

Medical Management of Reflux

The initial management of reflux should be to change modifiable behaviors. An individual needs to identify food and drink that is associated with worsening symptoms and avoid them. Meal times should be changed so that the last meal is 3-4 hours prior to bedtime. Sometimes the head of the bed can be raised to avoid night time symptoms. Smoking or any tobacco product should be discontinued. Weight loss is also a key component as well as wearing loose fitting clothing.

Should these changes not make a significant difference then medications are often used. There are a number of different medications that are prescribed or can be purchased as “over the counter” to suppress the production of acid by specialized cells in the stomach. Dosage and frequency can be adjusted to reach optimal results. Unfortunately, many people will continue to have symptoms despite receiving long term maximal medical treatment. This is one of the most common reasons patients are referred for surgical consultation. Recently, there has been some concern that prolonged use of PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) can lead to bone loss.

Common reasons patients and doctors choose surgical intervention are:

- failure to control symptoms despite maximal medical treatment

- profound esophagitis causing difficulty eating

- Barrett’s esophagus

- Desire to discontinue medications

How is the diagnosis made?

Although many cases of reflux can be determined by a patient’s clinical history and symptoms other test are needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Endoscopy (EGD): During this procedure an endoscope (long, thin tube with a camera on the end) is passed from the mouth into the esophagus and stomach. This procedure allows for direct visualization of the esophagus and can be used to determine how severe the reflux is by how injured the lining of the esophagus appears. Its also allows affected tissue to be biopsied to evaluate for Barrett’s esophagitis and to rule out cancer.

pH monitoring: There are a number of ways that this test can be performed. The gold standard has been placement of a small, thin tube through the nose until the end of the tube sits slightly above the connection between the esophagus and stomach. The tube has special features that can sense exposure to acid and relays this information to a box unit that the patient clips to his/her belt. The test is generally performed for 24 to 48 hours. Another commonly used device is the Bravo capsule that can be placed using endoscopic technique and loosely attached to the lower esophagus eliminating the need for a nasal catheter. The capsule will spontaneously dislodge and be passed out of the body, usually unnoticed. The results of this test will confirm the presence of acid reflux but may not pick up reflux that is the result of alkaline or basic fluid.

Upper GI/Esophogram: This is a radiology study where the patient swallows a chalky substance that allows the inside of the esophagus to be visualized and can provide anatomical information as well as information on esophageal motility. Motility is the coordinated movements that are made by the esophagus to push what we ingest down into the stomach. Long standing reflux can interfere with esophageal motility and establishing this pre-operatively may change the type of surgery that is performed. Esophageal Manometry: This test provides quantifiable information regarding the pressure generated by the esophagus during the propulsion of swallowed water. A tube is passed through the nose and into the esophagus. Side holes throughout the tube are used to locate the high pressure zone (lower esophageal sphincter), the length of the lower esophageal valve mechanism as well as determining the pressure generated by different areas of the esophagus.

The need for one or all of the above mentioned tests are based off of clinical symptoms and findings on endoscopy and esophogram. Your evaluation will be tailored to you.

What type of surgery is done to correct GERD?

The treatment of GERD is almost always performed using laparoscopic technique. Minimally invasive surgery allows the surgeon to visualize and manipulate the upper part of the stomach and lower esophagus in a way that even the largest incision cannot provide. The reason being that 50-60% of the stomach resides high up in the abdomen and is covered by the bony chest (ribs and sternum). Laparoscopic surgery provides a method to access the “hard to reach” area of the abdomen making the procedure much safer and with less post operative discomfort.

A key component of the procedure is to ensure that there is an adequate length of esophagus within the abdominal cavity. The ability to mobilize the lower part of the esophagus and upper stomach is simplified with the use of laparoscopic technique. Once the esophagus has been reduced into the appropriate position the muscle fibers of the enlarged opening of the diaphragm are brought together with sutures and occasionally a bio-prosthetic mesh (dissolvable mesh) is needed to reduce the potential for recurrent hernia through the diaphragm. Most surgeons agree that one of many forms of a “wrap” should be used to complete the procedure.

Gastric wrap also referred to as a fundoplication re-creates a one-way valve mechanism. The most commonly used wrap is the Nissen fundoplication whereby the upper stomach is loosely brought around the junction between the esophagus and stomach in a 360 degree fashion. Variations of the wrap are well described where the same area is covered by either a 180 or 270 degree fundoplication. The type of wrap used is often determined prior to surgery and is based off of the results of pre operative studies.

How long is the surgery?

No procedure is the same between two individuals with the same disease. Anatomical factors, medical/surgical history and the size of the hernia play a role in how long the procedure takes. In general, the surgical procedure takes 60-90 minutes.

What is the recovery?

Most patients are able to be discharged the day after surgery. Usually, within 3-5 days after surgery there is little discomfort and patients are able to move around and perform activities of daily living without discomfort. Strenuous exercise, lifting in excess of 15-20 lbs may be off limits for 2-3 weeks to reduce the chances of a recurrent hiatal hernia.

What are the dietary changes after surgery?

You will receive explicit instructions both before and after surgery about diet. You will progress from liquids to thickened liquids to soft foods and eventually back to a regular ‘heart healthy” diet. Details of the post operative diet will be provided prior to discharge.