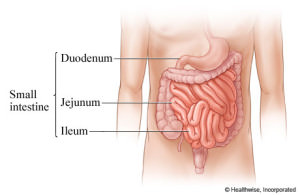

The small intestine is a long tubular organ that measures approximately 8 to 11 feet in length. The term “small intestine” refers to the narrow diameter of the organ relative to the colon or “large intestine”. The small intestine begins at the end of stomach and ends with its attachment to the colon. Anatomically the small intestine is divided into three areas: the duodenum, jejunum and ileum.

The small intestine is a long tubular organ that measures approximately 8 to 11 feet in length. The term “small intestine” refers to the narrow diameter of the organ relative to the colon or “large intestine”. The small intestine begins at the end of stomach and ends with its attachment to the colon. Anatomically the small intestine is divided into three areas: the duodenum, jejunum and ileum.

The primary responsibility of the small intestine is to continue the process of digestion (breaking down ingested nutrients to small particulates) and absorption (bringing the nutrients into the circulation). With remarkable efficiency the small intestine is able to absorb the overwhelming majority of carbohydrates, fats, proteins, electrolytes, vitamins and minerals.

Over the last several years a significant amount of research has focused on the profound effect the small intestine has on blood sugar levels. Bariatric surgery has elucidated a phenomena where in obese patients there is rapid improvement in blood glucose levels following bypass of the first portion of the small intestine. Only recently has the small intestine been viewed to play a major role in diabetes and the endocrine system.

Every day we ingest countless bacteria, parasites and viruses. The GI tract, with its large surface area, is a major portal of entry for potential infectious agents. The small intestine has a dense concentration of lymphocytes (immune cells) throughout its length acting as a barrier to the constant threat of infection. In essence, the small intestine is a major factor in our immune system.

Surgery for diseases of the small intestine

There are many conditions that can affect the small intestine. Fortunately, the most common maladies are self-limited and do not require surgical intervention. The most common indications for surgery of the small intestine are related to either obstruction, bleeding or perforation.

Obstruction

The most common cause of obstruction (small intestine blockage) is the result of scar tissue that has formed from previous surgeries. Scar tissue can be dense and firm to soft and filmy. The adhesions can form in cords or bands that pinch the small intestine or in ways that cause kinks. These obstruction will often resolve on their own with conservative management. In some cases surgery is warranted to release the adhesions and free the intestine. Focal areas of scar formation can occur in diseases of chronic, intermittent inflammation such as Crohn’s disease, referred to as strictures.

There are a number of benign and malignant masses that can form in the small intestine and create obstruction. Primary small intestine cancer is relatively rare in comparison to other cancers of the GI tract. Below is a brief list of tumors of the small intestine.

Benign Lesions: leiomyomas, adenomas, lipomas

Malignant lesions: carcinoid, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, GIST tumors, metastases from other site.

Bleeding

Blood in the stool may be attributed to an issue in the stomach, small intestine or colon. The stomach and colon are readily accessible with endoscopy and colonoscopy. It has been very challenging to identify sources of bleeding within the small intestine. There are a number of studies that have been used in the past with moderate success.

Small bowel bleeding can be slow and chronic or acute and fulminant. The source can be a malignant or benign mass, arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or the result of chronic inflammation (Crohn’s disease). Severe intestinal infections can also lead to significant blood loss. In addition, in predisposed individuals taking steroids, aspirin or other “blood thinners” are at higher risk for gastrointestinal bleeding.

Perforation

Perforation or a “hole” in the small intestine is considered a surgical emergency. For many decades a perforated duodenal ulcers was a common surgical emergency. Advancements in our understanding of peptic ulcer disease and newer antacid medications have reduced the incidence of duodenal perforations. In addition to ulcer disease, tumors, chronic inflammation, developmental abnormalities (Meckel’s diverticulum) and ingestion of foreign bodies (fish bones) can be a source for small bowel injury and perforation.

Laparoscopic small intestine surgery

Laparoscopic surgery can now be performed for a number of procedures related to the small intestine. Tumor resections, correction of strictures and lysis of adhesions is now well established and a preferable method for managing obstruction, bleeding and perforation.

Laparoscopic lysis of adhesions is a procedure performed to release the small intestine from scar tissue that is either causing an acute obstruction or chronic symptoms. The minimally invasive approach precludes a large mid-line incision and reduces the formation of new adhesions. In skilled hands, the entire small intestine can be evaluated and released from any adhesions.

In general, sites of bleeding, perforation or masses require a small bowel resection. The diseased portion of small intestine is removed and the healthy ends are reconnected. A surgeon experienced in laparoscopic suturing techniques can perform these complex procedures with minimal complications and maximal patient benefits.